Famous mountaineer Wasfia Nazreen popularly said that it was more difficult to walk on the streets of Dhaka as a woman than it was to scale a mountain. I have not done anything nearly as brave as climbing a mountain, but I know how mentally taxing and stress-inducing it is to simply exist as a woman in public in Bangladesh. Every choice we make can become the subject of scrutiny; any glance we exchange can be used to justify someone else’s inappropriate behaviour.

My earliest memory of being sexually assaulted in Bangladesh goes back to when I was 12, walking to my school in salwar kameez.

A few years ago, after I had submitted my photo to the agent of a popular Bangladeshi mobile financial services company to open an account, he called me of his own accord and asked me to send a different photo wearing an orna, because a photo wearing a T-shirt did not seem adequately “modest” to him. Being a passport-size photograph, it barely showed any part of my body below the neck, let alone the chest.

Recently, in granting bail to the assailant of the May 18 attack on a young woman at a railway station in Narsingdi, a justice of the High Court self-assuredly questioned whether in any civilised country a woman would ever wear a crop top and jeans to a rural railway station. Although the question is rhetorical, I would take the liberty to dissect it.

An online survey conducted by the UNDP and the Centre for Research and Information (CRI) has found that 87 percent Bangladeshi women have been publicly harassed. The remaining 13 percent women, who refused to answer, might also have been harassed, but chose to remain silent. Personally, I have never met a single Bangladeshi woman who has not been publicly harassed. So, what parameters did the judge use to conclude that a country where almost all women get harassed is the epitome of civilisation?

Going back to the basic legal definition, an offence is committed when the conduct (physical action such as touching) is paired with the mental element (for example, intention to commit the crime) of the accused. In no part of this equation is a victim’s conduct relevant – her outfit does not negate any part of the physical or mental element of the accused’s offence. The cardinal question relevant to the bail petition should have been whether a person who is infuriated at the very sight of a woman wearing a crop top and jeans in public would be a threat to other women’s safety. That question was either not raised by the judge, or even if it was, the assailant was not thought to be posing any risk to other women. So now she is free to go around terrorising and humiliating women who don’t conform to what is considered to be the “culture” of Bangladesh. If I didn’t know the context, just from the judge’s comments I would deduce that the victim was being tried for wearing jeans and a crop top in Narsingdi, an outfit apparently unsuitable for a “civilised” society.

The judge further implied that the perpetrator had the “right” to protect the culture and heritage of Bangladesh and permitted her exercise of such “right” by inciting violence to such a degree that it drove the victim to seek shelter inside the station office in fear of her very life. The court sent out this appalling endorsement to millions of people in Bangladesh, who wait only for an opportunity to hurl abuse at women. What part of a culture that necessitates women to literally fear a raging mob at the slightest instance of her dressing up somewhat unconventionally is worth protecting?

Considering that the judiciary is regressive enough to allow a woman to be abused seemingly in the name of preserving “culture,” where will it draw the line? Humiliating, terrorising, and sexually assaulting can soon lead to the killing of women. Would the court then also use the “right to preservation of culture” as a defence to murder?

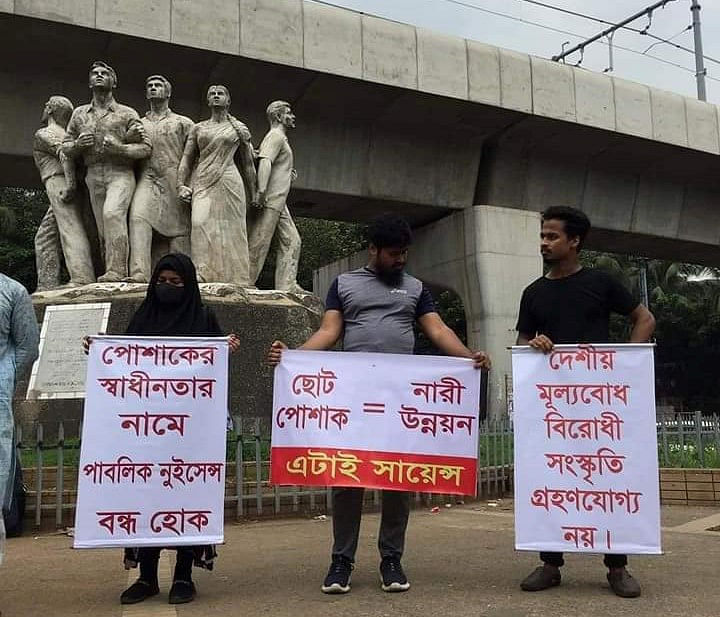

The hostility that the Bangladeshi public usually shows towards women, or anyone who seems defenceless, is in no way civilised. Why is the determination to protect the “culture” solely directed towards restricting women’s bodily autonomy, their right to movement and freedom of expression, rather than compelling the public to behave in a respectful and civilised manner? A hoard of people have supported the perpetrators’ crimes in the Narsingdi incident both online and offline. If violence against women in public places increases, our misogynistic judiciary will have played a significant role in it. As a woman and a legal professional, this is more terrifying to me than it is upsetting.

Every word spoken inside the courtroom has a knock-on effect. Judges’ words form legal precedents. A justice of the High Court in particular wields immense power to make or break societal barriers. With great power, there should at least come some self-awareness as to the effect a simple word can have on the day-to-day lives of millions of women, who, due to the court’s reductive comments, now stand on an extremely vulnerable position.

Being a woman in this country is the hardest job that we are assigned to at birth. Where injustice is rampant, the judiciary is often our only recourse. Such institutionalised victim-blaming, that shifts the burden on women and requires them to restrict their liberty and calculate their each step, instead of punishing the perpetrator, is like the very last lamp going out.

This opinion was originally published in The Daily Star (2022).