If you are arriving in Berlin from a more pristine, more conventionally “charming” tourist city, prepare to be shocked. Berlin is filthier than Amsterdam, less organised than Vienna, less flamboyant than Budapest. Even compared to its German counterparts, Berlin is much poorer as a city. In fact, luxury tourism is not Berlin’s strong suit. It’s the destruction, struggle and constant refurbishment of uncomfortable history that make Berlin stand out in your happy-go-lucky European touristy routine.

Berlin is ever-changing. A lot of its major infrastructures such as the City Palace and the Berlin Cathedral are being renovated. A few decades have gone by after the Fall of the Wall, and many have passed since the War, but this city has not stopped going through makeovers. However, the renovations are somewhat to the dismay of the Berliners, who have always been reluctant to accept the potential coverup or rewriting of history, no matter how ruthless or uncomfortable it is.

I joined a guided tour starting from the Oberbaum Bridge, the river Spree flowing diligently beneath us, Berlin TV Tower and the Berlin Cathedral visible in the vicinity. Had the feeble afternoon sun shone directly on the stainless-steel dome of the TV Tower, the sunlight would have reflected in the form of a cross over Berlin, a phenomenon the locals like to call the Pope’s Revenge. The TV Tower, which was the architectural magnum opus of Socialist Germany, was supposed to be a secular and communist symbol but has become the butt of an anti-communist joke due to the enmity between communism and religion.

We stopped at Bebelplatz, a public square close to Humboldt University. The Square now stands as a witness to one of the many notorious Nazi book-burning ceremonies which were carried out in German universities by the nationalist German Student Association in May 1933. In the middle of the stony square, there is a carefully pinned-down piece of glass. Peeking through the glass, I could see a library full of eerie, empty shelves underneath the floor—the ghosts of burned down history and knowledge. It’s a memorial dedicated to the sad demise of the ‘Un-German’ books. I tried to see Bebelplatz through the eyes of the fictional nine-year-old Liesel Meminger from Markus Zusak’s novel The Book Thief, who was made to witness the Nazi book burning. Until Berlin, that book was the closest connections I had to the War.

Near Bebelplatz is Neue Wache, a building that serves as a memorial for victims of war and dictatorship. It houses the popular Käthe Kollwitz sculpture ‘Mother and Her Dead Son’—undoubtedly an echo of Kollwitz’s own tragedy, having lost her son to the First World War. The statue sits right under an oculus (a hole in the ceiling), so that the unadulterated Berlin rain, sun, snow or cold may pour through it onto the statue, as it once did on the civilians during the War.

On August 13, 1961, East Berliners woke up to find barbed wire fencing along the borders to prevent East Germans from escaping from the repressive communist regime in massive numbers to the capitalist West Berlin. More than 100 people died trying to cross the Berlin Wall, one of whom was East German teen Peter Fechter. He was shot near Checkpoint Charlie in 1962 while trying to escape. He bled to death on a barbed wire fence, in front of the world media, too far inside the Soviet sector to be helped by the American soldiers, which eventually sparked a protest. Checkpoint Charlie was the most popular Berlin Wall crossing point between the East and the West side. I saw the whole shenanigan of eager tourists taking pictures with the 2001 replica of the original “You Are Now Leaving the American Sector” sign and the smiling fake soldiers guarding the checkpoint. It felt to me like a rather crude way to celebrate a historical location which had witnessed at least one tragic death.

A short walk away from the Checkpoint still stands a large section of the West Berlin wall. It’s in a shambles, as is evident from the iron bars peeking through in the middle. However, most of its decay is due to tourists chipping away famous relics of the barrier that once divided a nation, depriving future generations of the opportunity to see them.

Nazi architecture such as the former Reich Air Ministry (now German Finance Ministry) still exists in Berlin. The then largest office building in Europe survived the bombings nearly unscathed. Where the pillars were once decorated with myriad swastikas and Nazi flags flew proudly, now diplomatic decisions of German finances are made. The Germans cannot rewrite the Nazi history. I loved that instead of tearing down the Nazi architecture out of shame and remorse, they chose to utilise them as best as they could.

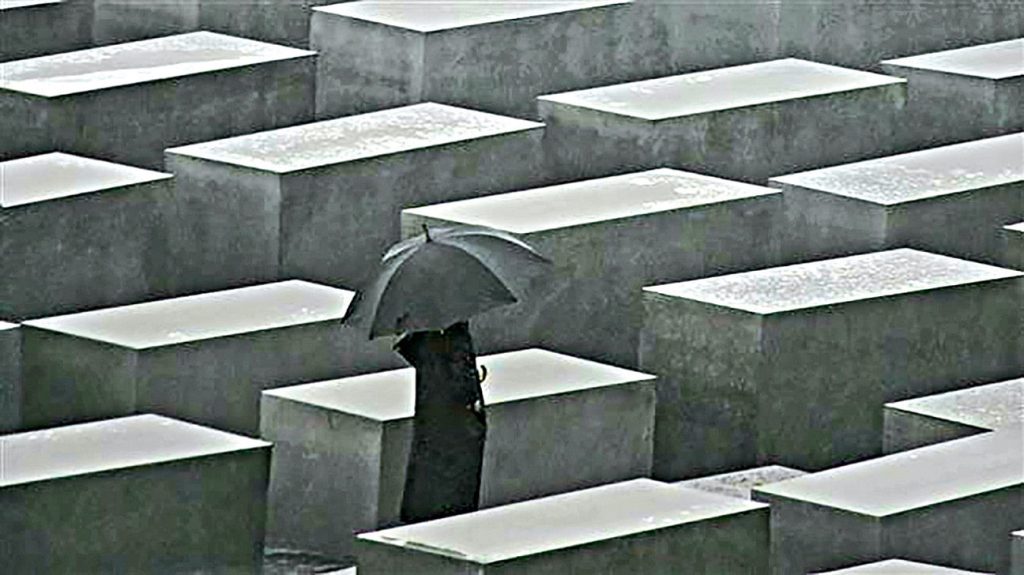

From there we went to the memorial dedicated to the crown jewel of the German tragedy, the Holocaust Memorial. Taking a walk between the rows of coffinlike concrete blocks evoked an unnerving melancholy in me. It made sense to then visit Hitler’s bunker. There on April 30, 1945, Hitler had committed suicide along with Eva Braun, whom he had married less than 40 hours earlier. In what I thought was a brilliant move, the place which once sheltered a wicked mastermind is now simply a parking lot. There is just a patch of grass on the ground above the bunker, making it as drab and unceremonious as possible so as to prevent anyone from turning it into a shrine for the man who lived there.

The guided tour finally ended at the Brandenburg Gate, where non-violent, pacifist protests led by about a million people over time led to the historic fall of the Berlin wall in 1989.

My trip to Berlin would be incomplete without visiting the East Side Gallery, the longest surviving piece of Berlin Wall which has now been turned into an artists’ canvas. Probably the most striking mural, out of the 101 in total, is the one of the former General Secretaries of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the Socialist Unity Party kissing, a reproduction of a photograph of their actual ‘fraternal kiss’ from 1979. Its German title translates into “My God help me to survive this deadly love”. The walls that caused death and destruction once, now serve as a powerful reminder to be kinder and united.

Memories of wars and walls hang in the air of Berlin. She has never had it easy, but that has not stripped Berliners of their kindness. Berlin moves forward with strength and precision. One day is not nearly enough to understand her complicated history and people, but if you are willing to look, Berlin will embrace you with open arms, probably because she wasn’t allowed to do it for so long. Berlin grows and changes and learns, staying true to the saying, “Paris is always Paris, Berlin is never Berlin”.

This travelogue was originally published in The Daily Star (2019).